December 17, 2025

I have issued two changes to my book regarding the water footprint of data centers:

A correction to a data point for a specific proposed data center in Chile

A correction and additional clarifications to a paragraph about the overall projected water use of AI

This post provides context on what happened, the new text, and additional reading on the water footprint of data centers.

#1. Data point correction

The data point in question appears in Chapter 12 of my book, which focuses on the environmental impacts of AI. Part of the chapter profiles a community in Cerrillos, Chile that has been resisting a proposed Google data center for years.

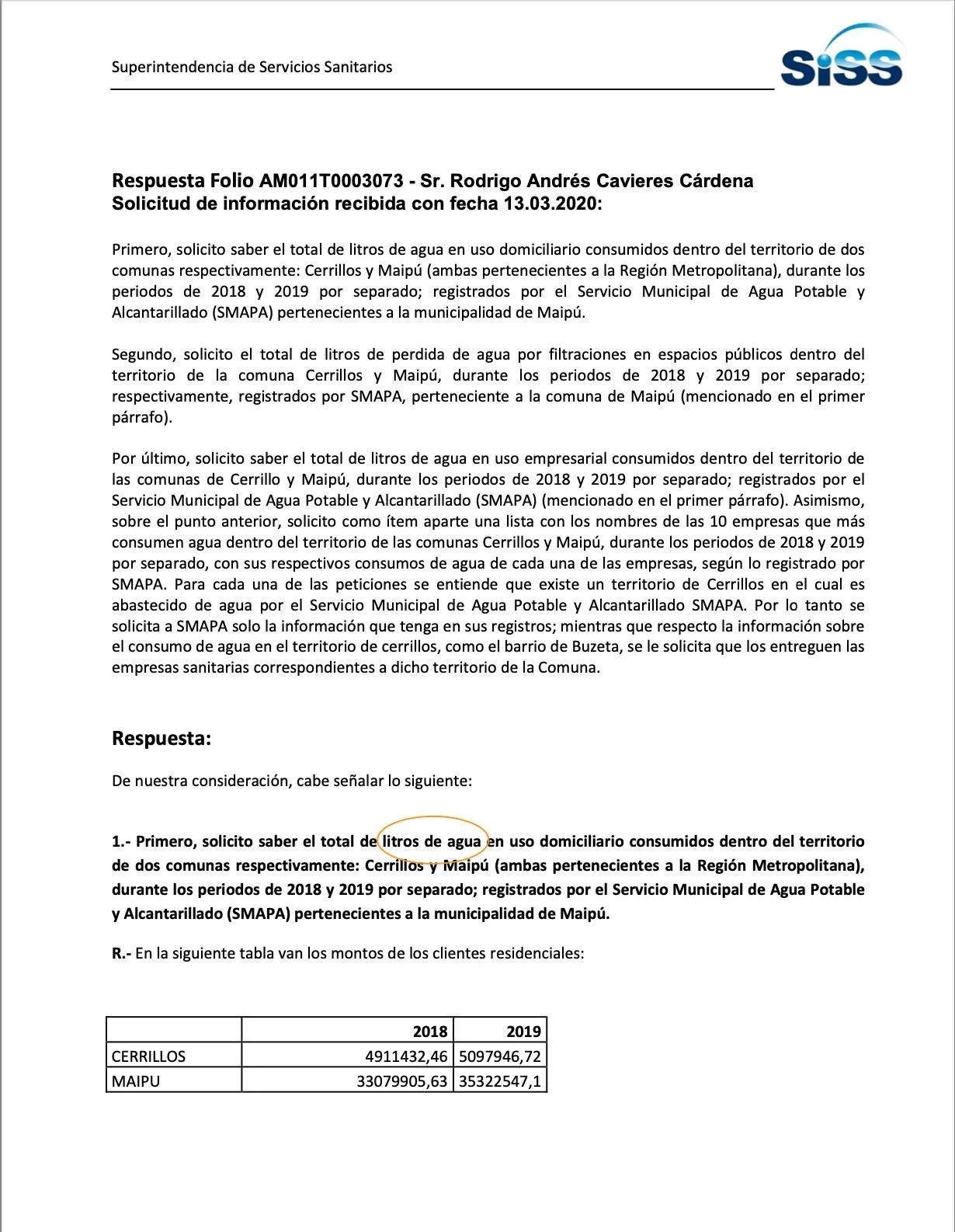

To describe the data center’s water footprint in lay terms, I included a sentence about how it compares to the water usage of the people in Cerrillos. For that calculation, I relied on a figure from a government document reporting Cerrillos’ residential water use. It turns out that the document used the wrong units. Where it states that its figures are in liters (“litros de agua” in Spanish, see image of document), the figures are in cubic meters, where 1 cubic meter = 1,000 liters. As a result the document understated Cerrillos’ residential water use by a factor of 1,000, which made my subsequent comparison between the population’s and data center’s water usage also off by a factor of 1,000.

Document from the Chilean government using “litros de agua” instead of cubic meters.

Thanks to reader Andy Masley for raising questions about the data point, leading my Chilean collaborator and I to investigate and confirm the error. Some people have fairly raised that if I had sense-checked the document’s numbers, I would have avoided this. I take full responsibility and will take steps to ensure this doesn’t happen again.

The corrected line, which I have submitted to my publisher and appears on page 288 of the hardback edition, now reads:

In other words, the data center could use more water than the entire population of Cerrillos, roughly eighty-eight thousand residents, over the course of a year.

Here is the math: The Google environmental impact report provided to the Chilean government stated that the proposed data center could use 169 liters of potable water a second, or 5,329,584,000 liters a year. With the correct units, the population of Cerrillos used 5,097,946,720 liters in 2019, the year Google sought to come in. 5,329,584,000 liters divided by 5,097,946,720 liters equals 1.045.

Some people have questioned the methodology of using Google’s figure (169 liters per second) as is, which represents the maximum amount of water that the company would be permitted to draw; those people have proposed discounting the figure. I am not using a discounted figure for two reasons. First, this is a proposed data center, and there isn’t strong scientific consensus around what discount to use; picking any particular discount would be speculation. Thus I believe it is more robust to reference the projected number Google provided to the Chilean government and use the phrase “could use.” Second, data centers can seek to increase their permitted water use after construction. For example, in Aragon, Spain, Amazon asked the regional government to increase their authorized water consumption at its three existing data centers by 48%, writing in its application that “climate change will lead to an increase in global temperatures and the frequency of extreme weather events, including heat waves.” Given the overall climate trends globally, this will likely become more common. (Source: Amazon’s application via The Guardian)

#2. Updated paragraph

On page 277 in the hardback edition, the updated paragraph will read:

So, too, is the extraordinary volume of minerals including copper and lithium needed to build the hardware—computers, cables, power lines, batteries, backup generators—and the extraordinary volume of fresh—even potable—water needed to cool the servers and generate the electricity to power them. (The water often used for cooling must be clean enough to avoid clogging pipes and bacterial growth; potable water meets that standard.) According to an estimate from researchers at the University of California, Riverside, surging AI demand could use 1.1 trillion to 1.7 trillion gallons of predominantly fresh water globally a year by 2027, or half the water annually withdrawn in the UK.

In the previous version, I incorrectly stated that AI demand could “consume” this much fresh water. The correct term is water “use” or “withdrawal,” and it is predominantly, but not all, fresh. I also added more context to the fact that the water footprint comes both from cooling the data centers and from generating the electricity to power them.

Additional reading

For more on the water footprint of AI, I’ve included a selection of links below, including some phenomenal reporting & new data that has come out since my book:

Making AI Less "Thirsty": Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models, arXiv, March 26, 2025, by Pengfei Li, Jianyi Yang, Mohammad A. Islam, Shaolei Ren

The environmental footprint of data centers in the United States, Environmental Research Letters, May 21, 2021, by Md Abu Bakar Siddik, Arman Shehabi and Landon Marston

The carbon and water footprints of data centers and what this could mean for artificial intelligence, December 17, 2025, by Alex de Vries-Gao

AI is draining water from areas that need it most, Bloomberg, May 8, 2025, by Leonardo Nicoletti, Michelle Ma, and Dina Bass

Revealed: Big tech’s new datacentres will take water from the world’s driest areas, The Guardian, April 9, 2025, by Luke Barratt, Costanza Gambarini, Andrew Witherspoon, and Aliya Uteuova

From Mexico to Ireland, Fury Mounts Over a Global A.I. Frenzy, New York Times, October 20, 2025, by Paul Mozur, Adam Satariano, and Emiliano Rodríguez Mega

Thank you to everyone who engaged in this issue. Factual accuracy is extremely important to me, and I’m grateful that this discussion has gotten us closer to the ground truth on these essential questions.